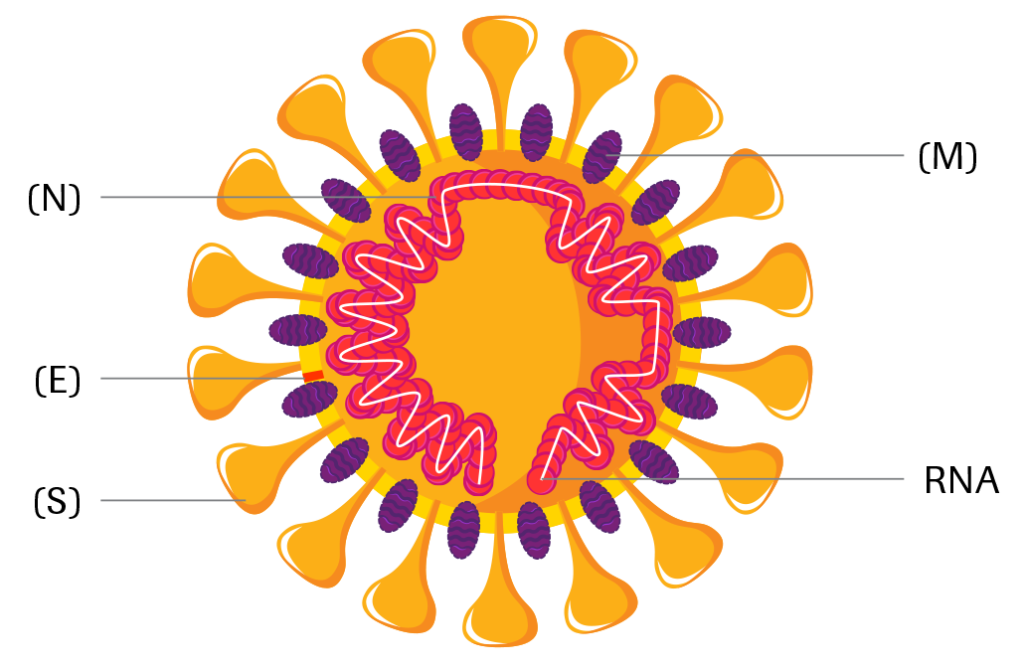

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is an enveloped, single-stranded RNA virus of the family Coronaviridae. Coronaviruses share structural similarities and are composed of 16 nonstructural proteins and 4 structural proteins: spike (S), envelope (E), membrane (M), and nucleocapsid (N). Coronaviruses cause diseases with symptoms ranging from those of a mild common cold to more severe ones such as Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by SARS-CoV-2 1,2.

SARS-CoV-2 is transmitted from person-to-person primarily via respiratory droplets, while indirect transmission through contaminated surfaces is also possible3-6. The virus accesses host cells via the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor, which is most abundant in the lungs7,8.

The incubation period for COVID-19 ranges from 2 – 14 days following exposure, with most cases showing symptoms approximately 4 – 5 days after exposure3,9,10. The spectrum of symptomatic infection ranges from mild (fever, cough, fatigue, loss of smell and taste, shortness of breath) to critical11,12. While most symptomatic cases are not severe, severe illness occurs predominantly in adults with advanced age or underlying medical comorbidities and requires intensive care. Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a major complication in patients with severe disease. Critical cases are characterised by e.g., respiratory failure, shock and/or multiple organ dysfunction, or failure11,13,14.

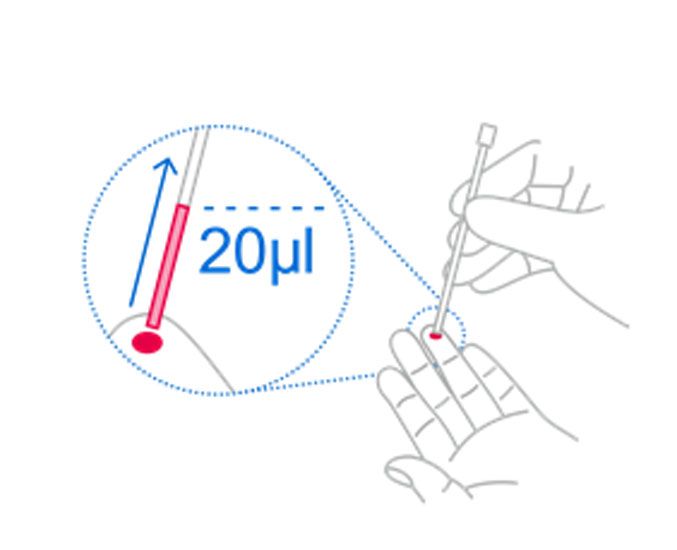

Definite COVID-19 diagnosis entails direct detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA by nucleic acid amplification technology (NAAT)21-23. Serological assays, which detect antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, can contribute to identify individuals, which were previously infected by the virus, and to assess the extent of exposure of a population. They might thereby help to decide on application, enforcement or relaxation of containment measures24.

Upon infection with SARS-CoV-2, the host mounts an immune response against the virus, including production of specific antibodies against viral antigens. Both IgM and IgG have been detected as early as day 5 after symptom onset25,26. Median seroconversion has been observed at day 10 – 13 for IgM and day 12 – 14 for IgG27-29, while maximum levels have been reported at week 2 – 3 for IgM, week 3 – 6 for IgG and week 2 for total antibody25-31. Whereas IgM seems to vanish around week 6 – 732,33, high IgG seropositivity is seen at that time25,32,33. While IgM is typically the major antibody class secreted to blood in the early stages of a primary antibody response, levels and chronological order of IgM and IgG antibody appearance seem to be highly variable for SARS-CoV-2. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgM and IgG often appear simultaneously, and some cases have been reported where IgG appears before IgM, limiting its diagnostic utility26,27,29,34,35.

After infection or vaccination, the binding strength of antibodies to antigens increases over time – a process called affinity maturation36. High-affinity antibodies can elicit neutralization by recognizing and binding specific viral epitopes37,38. In SARS-CoV-2 infection, antibodies targeting both the spike and nucleocapsid proteins, which correlate with a strong neutralizing response, are formed as early as day 9 onwards, suggesting seroconversion may lead to protection for at least a limited time34,39-42.